What’s shaking in the Vendée

In the afternoon of Friday 20 August 2021, the Vendée was shaken by several small earthquakes. One measured at a 3.5 magnitude and two more measured between 2.0 and 3.0 on the Moment Magnitude scale (Mw for short). The earth did not shake enough to have caused any significant damage, other than the odd statue or plate falling from shelves, or a crack in pavement or window, but it was felt as far south as Fontenay-le-Comte. Source

Based on the preliminary seismic data issued by the Réseau National de Surveillance Sismique (RéNaSS) the epicenters were located near Cholet (Maine-et-Loire, Pays de la Loire) and Les Herbiers (Vendée) but the exact magnitude, epicenter, and depth of the quakes may be revised as seismologists refine their calculations and more reports come in.

There were a further six smaller earthquakes under a 2.0. magnitude.

Do these sorts of tremors happen frequently? They do. An earthquake with a magnitude of 4.3 struck throughout the region of Pays de la Loire on Friday, June 21st, 2019. Before that, it was in February 2018 with a similar force.

The explanation for why earthquakes happen in the Vendée.

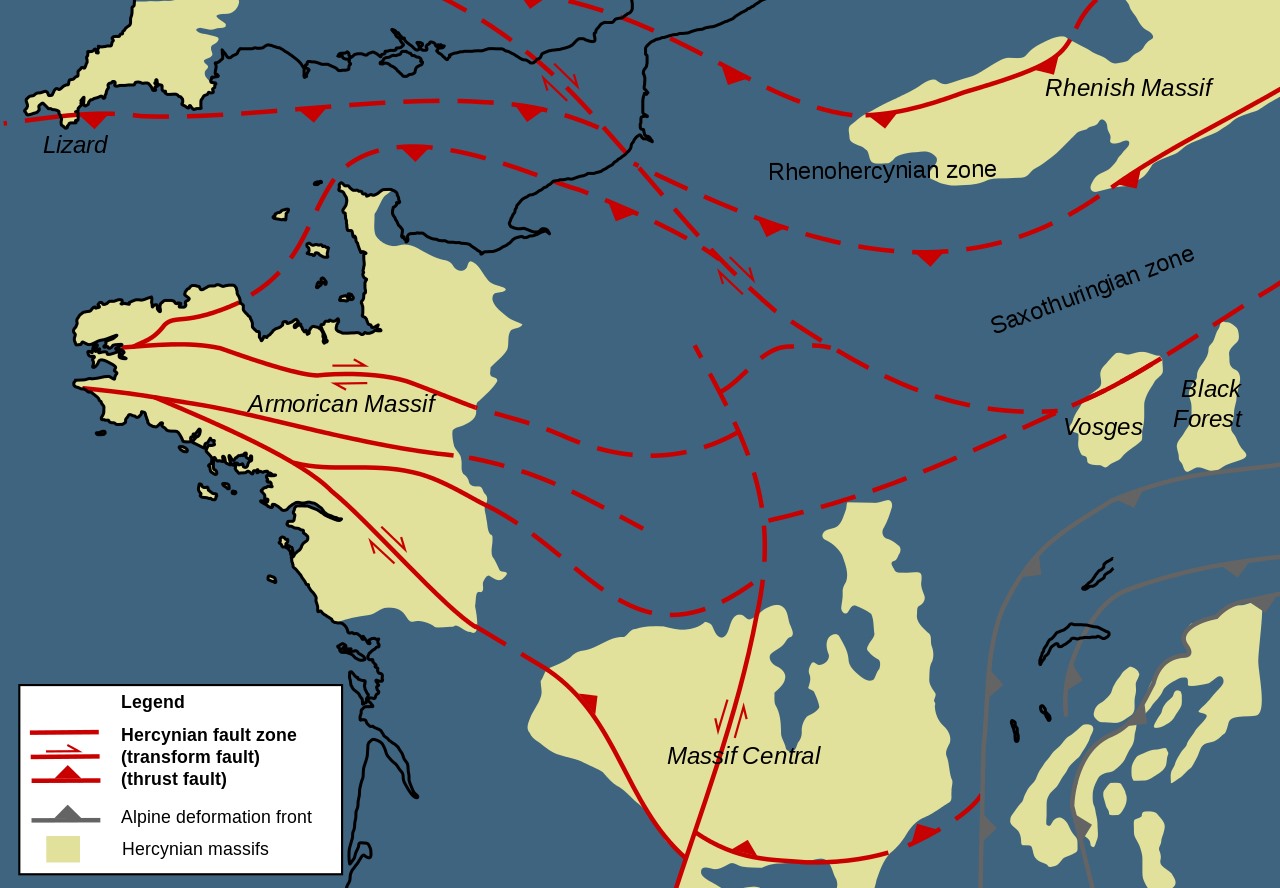

The region's coastal area is located to the south of the intraplate Armorican area. a geologic massif (an old mountain range) spanning Brittany, the western part of Normandy, and the Pays de la Loire. The name Armorican Massif comes from Armorica, a Gaul area between the Loire and the Seine rivers.

In the Vendée, the fault system curves from a south-east/ north-west into an east-west direction toward south-Brittany and further westward along the boundary fault of the West European basin and the British Shelf. The region’s tectonic history dates to Variscan times, a geologic mountain-building event some 370 million to 290 million years ago.

Due to its frequent seismic activity, this area in France is monitored both onshore and offshore.

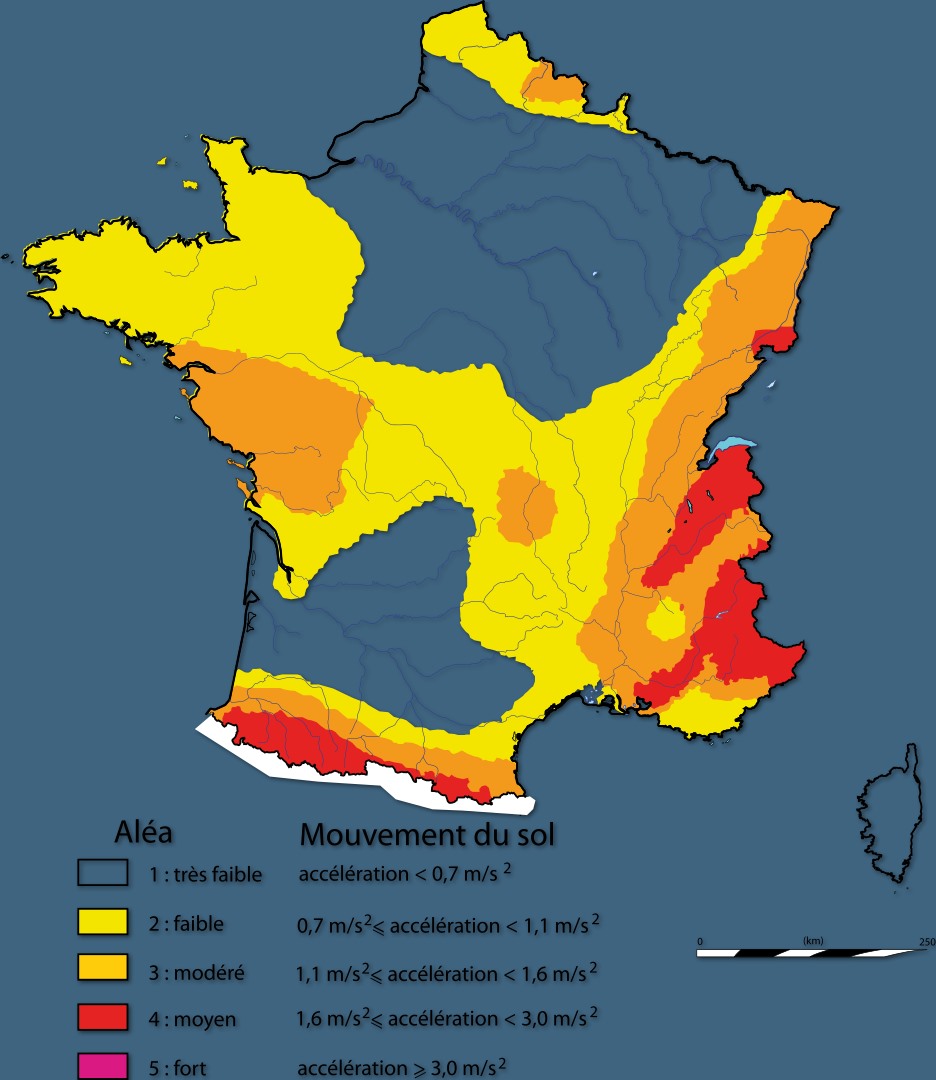

Seismic activity cannot be ruled out in many parts of France. In 2011 the government issued a Seismic Zone map showing the risk zones. As you can see from this map (still current – we searched high and low for an updated map but didn’t find one) – the Vendée is in Zone 3 – indicating a moderate risk of earthquakes.

Should it be cause for panic? No. The reason for monitoring seismic activity here has much more to do with risk prevention and protection (e.g. construction zones, location of bridges, pipeline transport) as well as enforcing building safety standards and construction materials.

Keep reading for things you might like to know and why it's helpful to report your earthquake experience.

Areas with earthquake risk in France (wikipedia)

Fault lines in France (wikipedia)

A few things you need to know:

- UTC stands for Coordinated Universal Time and is the same as GMT (Greenwich Mean Time), however, it doesn’t take the summer time change into account. So, using the August 2021 earthquake as an example, the event took place on 20/08/2021 at 15h47, and the universal time is reported as the earthquake having taken place on 20/08/2021 at 13h47.

- Why earthquakes are now referred to as Moment Magnitude (Mw) as opposed to Richter? According to the the USGS.gov website: "Moment is a physical quantity proportional to the slip on the fault multiplied by the area of the fault surface that slips; it is related to the total energy released in the earthquake. The moment can be estimated from seismograms (and also from geodetic measurements). The moment is then converted into a number similar to other earthquake magnitudes by a standard formula. The result is called the moment magnitude. The moment magnitude provides an estimate of earthquake size that is valid over the complete range of magnitudes, a characteristic that was lacking in other magnitude scales."

- It's good to know the actual depth of an earthquake. Where computations are too unreliable, the world-wide average depth of earthquakes is used 10km (a reliable average depth at which the earth plates shift)

- News reports tend to err on the side of sensation.

Here you see the fracture and deformation of the layers of rock. In an active geologic fault, stresses at the points of fracture build up and when released, the ground shakes.

Reporting your (anywhere in the world) earthquake experience!

Why should you? Actually, Internet users are an important source of information in the collection of data used to form a more detailed snapshot of earthquake-prone regions. The DYFI (Did You Feel It?) citizen science webpage for instance, was developed to get more complete descriptions of any occurrence world-wide, the damage caused and perhaps most importantly the effects of an earthquake on the community. Data submitted by the ‘average Joe’ is even used to create maps and graphs in ‘real-time’ or instantly. DYFI encourages people to share their experience through a short questionnaire (just tick the boxes) – even if your community was already represented by another user. The more info is received on an area, the more reliable local information becomes.

Even if you didn’t feel the earthquake, your report can be important in gauging the percentage of ‘felt’ vs ‘not-felt’ experiences, as well as to gauge of where that boundary exists.

Report your earthquake experience here !

- Click on the earthquake that you think you felt, and

- Then select the "Tell Us!" link.

- If you don't see the earthquake you think you felt listed, use the green "Report an Unknown Event" button

Current seismogram displays France:

https://renass.unistra.fr/

What to do in case of an earthquake?

Indoors?

- DROP to the ground where you are. Research has shown that most injuries occur when people inside buildings attempt to move to a different location inside the building or try to leave.

- Take cover under a sturdy table or other piece of furniture; if that's not an option, cover your face/ head with your arms and crouch in an inside corner of the building.

- Stay inside until the shaking stops

- Stay away from glass, windows, outside doors and walls, and anything that could fall

- If you’re in bed, stay in bed. Protect your head with a pillow, but roll away from any light fixture that could fall

- Be aware that the electricity may go out, there may be gas leaks, and sprinkler systems or fire alarms may activate.

Outdoors?

- Stay outdoors

- Move away from buildings, streetlights, and utility wires. The greatest danger exists directly outside buildings, at exits and alongside exterior walls.

In a vehicle?

- Stop as quickly as safety permits and stay in the vehicle.

- Afterwards, proceed with caution: roads, bridges, or ramps may have been damaged so don’t use them

Trapped under debris?

- Cover your mouth with a handkerchief or clothing.

- Tap on a pipe or wall so rescuers can locate you. Use a whistle if one is available. Shout only as a last resort. Shouting can cause you to inhale dangerous amounts of dust.

What not to do in case of an earthquake?

- Do not use a doorway except if you know it is a strongly supported, load-bearing doorway (inside doorways don’t qualify)

- Do not exit a building during the shaking.

- DO NOT use the elevators.

- In a vehicle, avoid stopping near or under buildings, trees, overpasses, and utility wires.

- If you are trapped under debris, do not light a match! And do not move or kick up dust.

Do you feel informed? Great! Next time the earth shakes, rattles and rolls under your feet you’ll know the what and the why. Just remember that the last major historical earthquake in the Vendée (M6) occurred on January 25th, 1799. And the average for a (small) earthquake to occur in the Vendee is about every 2 years.

Sources: Geodynamic Models: An Evaluation and Synthesis By R. W. Van Bemmelen, https://www.emsc-csem.org/, https://earthquake.usgs.gov/, https://renass.unistra.fr/, https://www.ready.gov/earthquakes

Share this Post