The Vendee Wars. 1793 - 1799

Introduction

The history of the Vendée Wars was not written by the victors, it was completely written out of French history, and until recently denied by the French government, it is still not part of the school history curriculum, but is well documented. When Solzhenitsyn opened the official Vendée Memorial at Les Lucs-sur-Boulogne in 1993 the event was ignored by central government, as well as by most of the mainstream French media.

The war was the first 'total war' in modern history, in which men, women and children were involved. It was also the first modern war in which regular troops were repeatedly beaten by mainly unarmed (no firearms) peasants. It was a savage affair in which each side were guilty of atrocities. The name of the region at that time was Bas-Poitou, and it was a poor rural region. As well as peasants, it was inhabited by impoverished aristocrats, petit bourgeoisies and poor priests; so the social inequalities were less marked here than elsewhere in France.

The revolution of 1789 was at first full of hope, with a genuine wish for reform, even the English hailed it as a triumph of reason over superstition and privilege. That summer, The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen was adopted by the new National Assembly.

Who could argue with?

The more the Jacobins took control in Paris, the more events began to escalate. No political or state organisation can control the religious faiths of its people, and the population of the Vendée Militaire, (the name given to the area of armed resistance, south of the Loire) and Brittany was devoutly Catholic. However, controlling faith was exactly what the Republican government tried to do, which engendered deep resentment that grew over the years.

1790-1793

In 1790 local government was abolished, followed by what was a considerable blow to poor Catholics, the vote on 12th July for The Civil Constitution of the Clergy. This was state control of their church, with the confiscation of its property, their traditional priests were banned, and all religious orders suppressed. In 1791 the Ecclesiastical Oath forced priests under state rather than episcopal control. Those who refused, (and in the Vendée most refused) were outlawed and replaced by state 'priests'. 1792 saw an increase in taxes, and in January 1793 the execution of the king; then the introduction of conscription in February caused great opposition.

Although there had been sporadic riots and easily suppressed uprisings since 1792, the final spark that ignited this smouldering resentment into a barbaric war, was the prohibition of public worship and the closing of all Catholic churches on 3rd March 1793. This caused no inconvenience to the nobles, who had their own private chapels in their homes (as at La Chabotterie), as well as their personal priests. However, without access to churches, the ordinary devout Catholic could not fulfil their religious obligations. In response, the ordinary people of the Vendée Militaire defied conscription. Paris ordered Republican troops and National Guards to enforce conscription by ballot.

On 11th March, Republican soldiers billeted at Machecoul were massacred. That same day the people of St-Florent-le-Vieil turned their horizontal scythe blades into very effective vertical weapons, and routed the government troops, who were supported by cannons. Despite sustaining heavy casualties, the villagers kept advancing, until the soldiers’ nerve broke, as did their ranks, and they fled. The Vendée Wars had begun.

1793

There were uprisings in many parts of France, but they only lasted at the most a few weeks. Only in the Vendée and Brittany was there prolonged insurrection, with the Chouans waging a predominantly guerilla war. The Vendéens invited local nobles with military experience to lead them, and although some refused others willingly agreed.

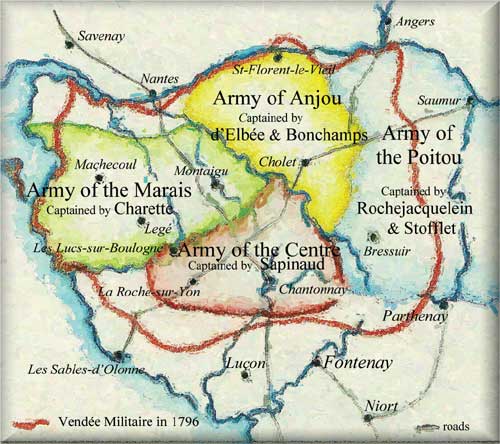

When asked by his local men to lead them, the twenty year old La Rochejaquelein spoke the immortal words: “I will show myself worthy. If I advance follow me; if I flinch, cut me down: if I fall avenge me.” The uprising was so spontaneous and popular that within a few weeks the rebels had four large armies, which won one victory after another.

Their first major battle was on 19th March, when a Republican column of over 2,000 infantry, 100 cavalry, and some cannon, marching to re-enforce Nantes, was ambushed and routed by part of the Army of the Centre, at Pont-Charrault. With this victory came thousands of badly needed muskets, as well as ammunition, horses and cannon.

Recruitment areas of the Vendéen fighters

On 20th March the four armies united and named themselves ‘The Grand Catholic Army of the Vendée’, the word ‘Royal’ was added later. Towns began to fall, first Bressuire on 2nd May, Fontenay on 25th May, and the rebels reached Niort. In the north, Angers fell on 18th June, and there was panic in Paris.

Seven days earlier the rebels elected the humble Jacques Cathelineau from Le Pin-en-Mauges as their Commander-in-Chief. They unsuccessfully attacked Nantes, but on the second day of the battle Cathelineau was mortally wounded. and d’Elbée became their new Commander-in-Chief.

The Vendéen fighters, also known as ‘whites’ or ‘brigands’ had the habit of returning home after a battle to tend their land.

At Waterloo, Napoleon had a total of 60,000 men to fight Wellington’s regulars. Yet, in October 1793, Paris sent an army of 115,000 to fight the rebels in the Vendée Militaire, who were only 60,000 ill-equipped and untrained fighters. The insurgents were supported by 2,000 irregular cavalry, and a few cannon; and those with muskets were better shots than any French or British infantryman of the day.

The battle was outside Cholet on 17th October and raged all day, at first the Vendéens were winning, but in the afternoon, due to tactical errors, they were forced to leave the field. It was no rout, they did so in good order. Sadly for the rebels, three of their generals, d’Elbée, Bonchamps and Lescure were badly wounded in the battle, the latter two mortally so.

The rebels decided to cross the Loire, and head for a port to await help from England. This journey was called "La Virée de Galerne." d'Elbée was taken to Noirmoutier to recover from his wounds, and Henri La Rochejaquelein became the new Commander-in-Chief of the rebel Army.

The Vendéens and Chouans were unable to capture Granville, but just as they headed for home, the sails of the English fleet appeared, too late, on the horizon. Weakened by hunger and dysentery the Vendéens had to fight every mile of the journey back, constantly harassed by government cavalry and sharp shooters. Despite their plight, La Rochejaquelein won three battles on their homeward journey, but they were unable to re-cross the Loire because of a lack of boats.

Republican troops forced the rebels back north to Le Mans where, severely weakened, on 12th December they were defeated. On 23rd December the remnants of the Grand Catholic and Royal Army were annihilated in the woods and marshes of Savenay, where no quarter was given by the Republicans. Over 2,000 rebels managed to escape and find their way back home, only to look with horror on the results of General's Turreau's 'douze colonnes infernales'.

For nine months, from January 1794, those 'twelve columns of hell' crisscrossed the Vendée Militaire, often revisiting the same places. Their orders were quite simple and very explicit; "Leave nobody and nothing alive." This applied to republicans and rebels alike. Crops and houses were burnt, and the department was re-named "Vendée."

In January a reign of terror began in Nantes and Angers, where there was mass murder by drowning in the Loire, by guillotine and shooting. General Waterman (known as 'The Butcher') boasted to the Convention in Paris:

"...there is no Vendée. It has perished, with its women and children, under our sword of freedom. Following your orders, I have crushed the children under our horses' hooves, and massacred the women - they will bear no more children for those brigands. I have not taken a single prisoner."

Wounding Gen. Beaupuy Château-Gontier

Wounded General Lescure

La Virée de la Galerne

Battle of Le Mans

On 6th January 1794 Maurice d'Elbee was executed, and on 28th January La Rochejaquelein was killed in action, and Stofflet became their last Commander-in-Chief.

1795-1799

The Vendéens were not deterred, and they conducted such an effective guerilla campaign that the Paris regime finally sued for peace.

A treaty was signed on 17th February 1795 but broken by Charette on 24th June. On the following day the promised help from England arrived at Quiberon and Pont-Aven, too little and too late, due to the prevarication of the French aristocratic emigrants.

The following year, first Stofflet, then Charette were executed, and the war petered out.

Religious freedom was still officially denied, and so the war began again on 15th October, 1799. Republican villages and towns were seized, even Nantes fell on 29th October, but the rebels were too weak to hold it.

Execution of Charette

Signing of the Concordat

1799

On 9/10th November Napoleon Bonaparte seized power in a coup d'état. He had great respect for the Vendée people and called their war "le Combat des Géants." He fully understood that their fight was not a struggle against the revolution, but a fight for the preservation of their liberty and freedom for their religion.

Bonaparte immediately began talks with the Vendéen religious leader Abbé Bernier, and set about repairing relations with the Catholic church. By December full rights of worship were restored to the church, not only in the Vendée, but in the whole of France, and church bells rang again.

The Concordat signed on 15th July 1801 between Napoleon Bonaparte and the Pope made these rights official. In the Concordat the French Government acknowledged "Catholicism as the religion of the great majority of the French." In the end the Vendéens won the right to practice their faith.

Bonaparte also exempted them from conscription, gave them full indemnity, and assisted the reconstruction of the department. To facilitate the supervision of this region, the capital was moved from Fontenay to the then very small village of La Roch-sur-Yon.

Two further attempts were made to rekindle the wars, in 1815 and 1832. However, neither had validity, were ill-conceived and unsuccessful, with little support from the Vendée.

"REMBARRE!"

To-day, both the right and left of French politics find the Vendée Wars problematic. The idea that any religious faith could be important to peoples' lives is anathema to the atheists and communists of the left, who site conscription as the cause, and call them civil wars. The right on the other hand, site the execution of the king, and a desire for the restoration of the monarchy, so refer to the wars as counter-revolutionary wars. Neither acknowledges the well documented fact that the Vendée Wars were fought by a Christian faith for religious freedom.

At the twilight of the pre-revolutionary Old Regime, questions about what it meant to be a Catholic and why the church mattered, often stood at the heart of most political debate in France. Yet the combination of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, the execution of the king, and the introduction of conscription, would not have been sufficient to ignite a popular revolt. However, the effects of the implementation of the Ecclesiastical Oath, and from 3rd March, 1793, the closing of churches, combined with the prohibition of public worship, were the sparks that ignited the Vendée Wars.

On 19th July, 1793 the governing council of the rebels issued a decree of their intention that: "Desirous, as far as we are able, of re-establishing the Catholic religion and allowing it once again to flourish."

There are hundreds of documents available for reference (military dispatches, official correspondence, contemporary letters, and copies of procès verbaux still available for study), in the Archives National, the Ministry of War, and the provincial archives of Nantes, Angers and elsewhere.

Lawrence John Dunn

Share this Post